ABSTRACT:

The first prime numbers form groups containing all other primes. This is shown first. An analysis of the groups delivers a statement about the distance between prime numbers, an extension of Bertrands postulate, Goldbachs conjecture and an algorithm for calculating primes and for prime factorization. The results are compared with Riemanns Zeta-Function.

1. Introduction

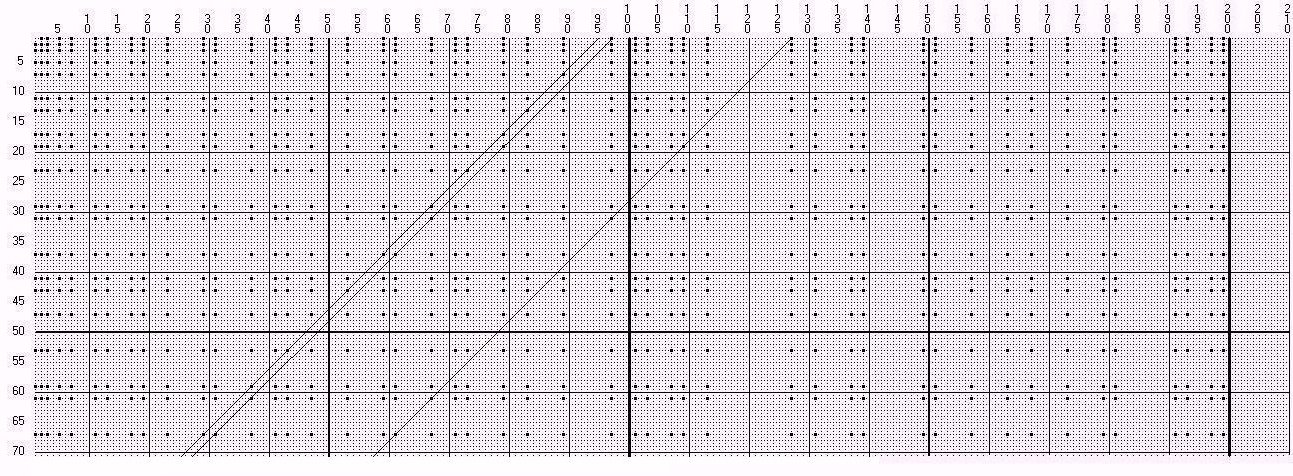

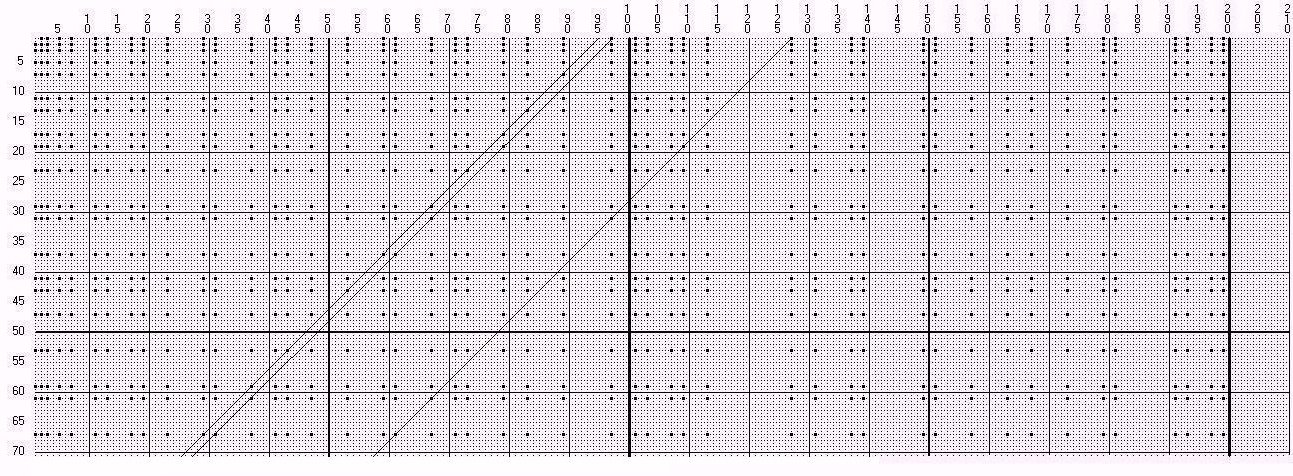

A integer > 1 which has no natural divisors than itself and 1 is called a prime number. Many papers have been published on the arrangement of prime numbers. of theirs distribution of primes is shown in the so-called Ulam's spiral or prime number spiral [1]. It was founded in 1963 by the Polish mathematician Stanislaw Ulam during a scientific lecture scribbling rows of numbers on a paper. He began with the '1' in the center and the he continued in spiral order. When the prime numbers are marked, we find that many primes are on diagonal lines. This is shown in the picture (Fig. 1). If the only even prime number 2 is ignored, the effect becomes even more appearent. This picture stimulated me to look into a further systematic arrangement.

If the only even prime number 2 is ignored, the effect becomes manifest more obvious. This has me motivate to consider another systematic array.

2. Prime Residue Classes

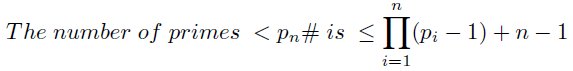

Another system of the prime numbers becomes visible in certain prime residue classes, in the following also called 'stamps'. Some of its properties will be described now. Let p denote a prime number and p1 , p2 , . . . are the prime numbers in ascending order. Analogous to the factorial n! a product of prime numbers (also named primorial) p# is defined by

This is the product of the first n primes. I don't use the index and denote such a product by p# if it doesn't depend on the number n.

2.1 The 6-Stamp

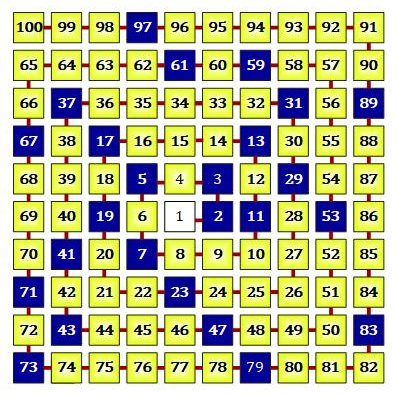

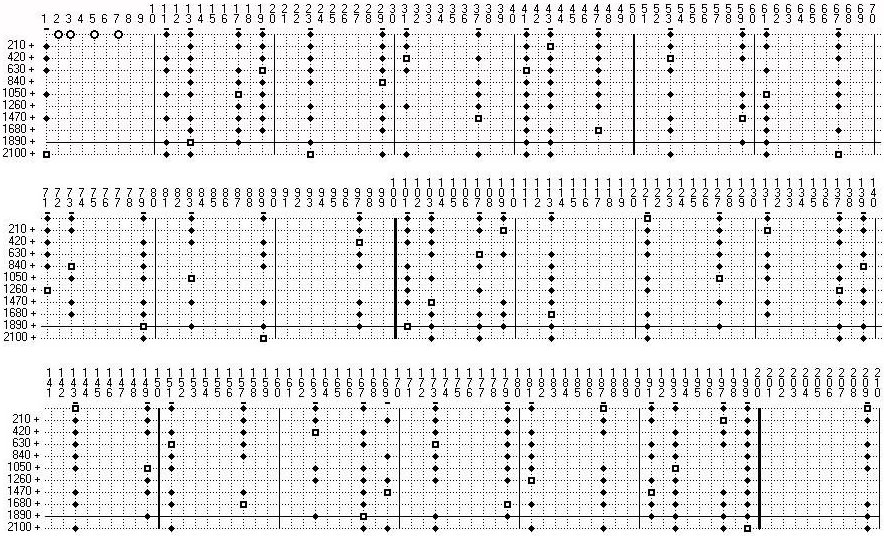

In many articles about prime numbers it is mentioned that all prime numbers > 3 have the form 6k - 1 or 6k + 1; k = 1, 2, 3, . . . . Figure 2 shows this up to the number 30. In the first line, the baseline, i.e. the stamp (to which the "1" always belongs), the first 6 numbers are shown. The other lines again contain 6 numbers each. A number at the intersection of row and column is the sum of the number at the left edge and the number at the top edge. The 2 circles with white inner area are the prime numbers 2 and 3. The black dots are the remaining prime numbers < 30. The two numbers 2 and 3 are the prime divisors of 6. The numbers 1 and 5 are called the prime remainder classes modulo 6.

The number of 6 columns results from the product of the first 2 prime numbers 2 and 3. All prime numbers except 2 and 3 lie on the first and fifth column, the '6-stamp'. The numbers on the other columns are divisible either by 2 or by 3.

2.2 The 30-Stamp

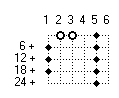

In the formation of 30 numbers each, the product of the first 3 primes 2, 3 and 5, the primes (except 2, 3 and 5) are on definite columns. This fact is showed in figure 3 up to the number 210 [ [see for example in: "Kurt Diedrich: Primzahl-Lücken-Verteilung ohne Geheimnisse? www.primzahlen.de"]. A grafic representation is chosen to illustrate the correlations and comprehensible for all who are interested on this problem..

Again the black points are the primes < 210. For reading

and destinating a number, on the left side and on the top numbers are marked.(on the numbers at top the numerals are written among themselves). On the crossing of row and column is the number, resulting from the sum of the numbers at the left and the top. The primes 2, 3 and 5, the prime divisors, are pictured as 3 circles with white center. They don't belong to the stamp, the prime residue classes. On the columns of the prime divisors are no other primes. The lines in the figure are dotted. Every tenth line is a continuous line for better orientation. For the numbers with white center I will go in more detail at the end of this section.

If one designates such a stamp with S, then one can designate the 30-stamp with the help of the definition of pn# also with S5# . Its elements are the 1 and the prime numbers, except 2, 3 and 5 in the 1st line, the baseline. In Figure 3, they are marked with a horizontal bar. I denote these by s1, s2, . . . ,sm . We have 8 columns containing all primes except 2, 3 and 5. Here therefore is m=8. Only the elements in the first row are part of the stamp. All primes > 30 have the form sj + 30k; j = 1, . . . ,m; k = 1, 2, 3, . . . . In figure 3 there are another 6 lines, which show how to make the next stamp.

2.3 The 2-Stamp

The smallest stamp that can be formed in this way consists of two columns. The first row contains the 1 and as the first prime number the 2. The next prime number 3 is in the second row. Figure 4 shows only 3 rows.

The first column contains all primes > 2. This is well known:

All prime numbers > 2 are odd. If you examine the stamps more closely, you will that they build on each other. For example, the numbers of the 30-stamp are created by selecting the numbers from the columns 1 and 5 of the 6-stamp in the first 5 rows and eliminating from this selection those numbers, which are divisible by 5 without remainder. These are the numbers 5 and 25.

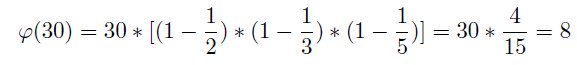

2.4 The 210-Stamp

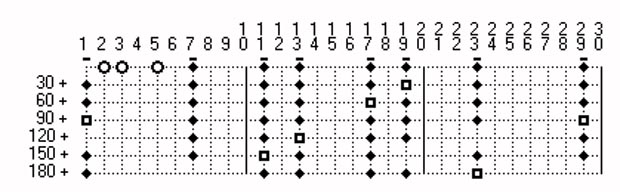

In the same way the 30-stamp is used to create 210-stamp or S7# is generated. From the columns of the 30-stamp all numbers up to 210 are selected and those that are divisible by 7 without remainder are not included in the stamp. This is how the numbers of the 210-stamp are obtained. It can be recognised in figure 5 that the prime numbers except 2, 3, 5 and 7 are lying in these columns. The subset P7 = {2, 3, 5, 7} of the prime numbers forms the stamp.

Definition(2)

Base-primes in the following are named these primes p1, p2, . . , pk which not belong to the stamp.

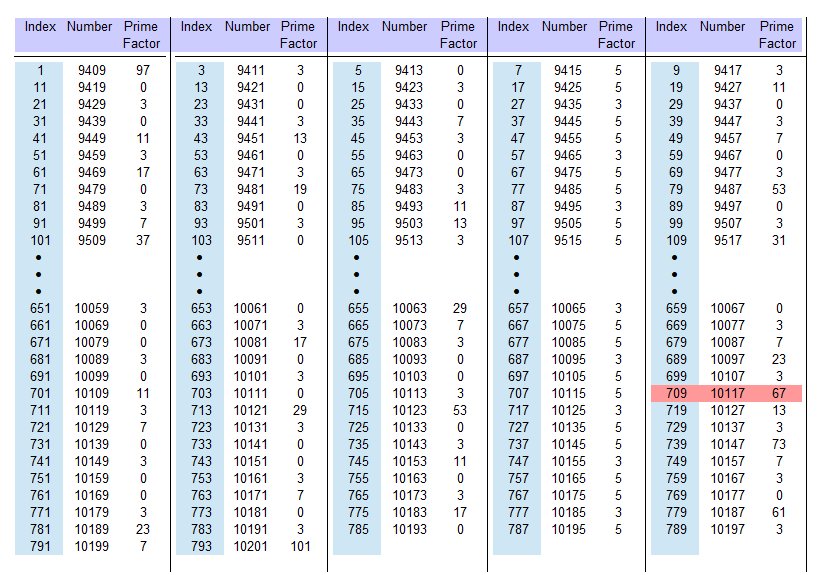

For the stamp S7# these are the primes 2, 3, 5 and 7. Only the 'one' and the other marked numbers in the first column belong to the stamp. The primes > 210 up to 2310 are additionaly shown in figure 5.

For reasons of space the figure 5 consists of 3 parts 70 numbers each. The first 4 primes do not lie on the columns of the stamp. The are marked by circles with white center. The numbers marked by squares with a white inner are divisible by 11 . They are important for the formation of the next stamp. In the stamps S2#, S3# and S5# all numbers except 1 are primes. In contrary in this stamp the first time the fact appears that not all numbers of the stamp are prime. This is important for further explanations. They are the numbers 121, 143, 169, 187 and 209 in this stamp . They are products of primes > 7. All elements of the stamp S7# are indicated with a dash. Accordingly such numbers appear also in higher stamps. In the following I will refer to this stamp S5# because much of primes can be deduced therefrom.

2.5. The number of elements

First we look at the number of elements in the stamps. The smallest stamp S2# has only one element s1 = 1. In the next stamp S3# there are the primes > 5 on 2 columns. This stamp contains two elements: s1 = 1 and s2 = 5. As S5# has a formation of 30 we build this stamp from the first 5 rows of S3# . Exactly one of the numbers s, s + 6, s + 12, s + 18, s + 24 on the column s1 is divisible by 5 . The numbers s1; s1 + 6; s1 + 12; s1 + 18; s1 + 24 are also in one column and exactly one of these has the divisor. These two numbers are not included in the stamp S5# . Therefore we get 8 elements in this stamp. If we continue in such procedure and go over to the next higher stamps, we get the following result:

As we see on the stamps, for instance on the 210-stamp, the first primes (here 2, 3, 5 und 7) don't belong to the stamp. The stamp however is exclusively formed by these primes.

Definition(3):

The numbers coprime to pi; (i = 1, , , n) ![]() are named stamp

are named stamp ![]() . A stamp

. A stamp ![]() is build with the primes p1, p2, p3 , , , pn of the subset Pn = 2, 3, , , pn . These primes are are named prime divisors of the stamp

is build with the primes p1, p2, p3 , , , pn of the subset Pn = 2, 3, , , pn . These primes are are named prime divisors of the stamp ![]() .

.

Definition(4):

a mod m is named prime residue class,

if a and m are coprime, i.e. ged(a,m)=1.

On the stamps it is a matter of prime residue classes .

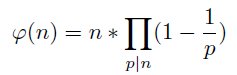

We look for example at the stamp S5#. The prime divisors of 30 are 2, 3 und 5. Euler's φ-Function computes the number of positive integers less or equal to pn# that are coprime to pn#.

p|n are all prime divisors of n.

With this formula the number of prime residue classes also can be computed. For example we get

and the 8 elements are 1, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23 and 29. Exactly these are the elements of S5# (Fig. 3).

The numbers 1 and ![]() always are part of a stamp. In the stamp S7# the elements sj are coprime to the primes 2, 3, 5 und 7. For sj is valid:

always are part of a stamp. In the stamp S7# the elements sj are coprime to the primes 2, 3, 5 und 7. For sj is valid:

The results recur in the next intervals 211 to 420, 421 to 630 etc.. We can therefore speak about these intervals as a copy of the first interval 1 to 210, just like a stamp an impressed pattern passably copies. Before continuing I will refer to a well known theorem. It is the

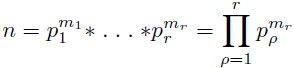

Theorem 1: Main theorem of the elementary theory of numbers:

Every number n > 1 , n ∈ N , has exactly one representation

with primes p1 < p2 < pr

and exponents m1 ≥ 1, m2 ≥ 1 , , , mr ≥ 1.

Even Euklid (325-265 BC.) has recognized that a prime number which

is a divisor of a*b also is divisor of a or a divisor of b. The main theorem of the elementary theory of numbers has been proved by C. F. Gauss ( 1777-1855) and E. Zermelo (1871-1953).

We look at a stamp

![]() with elements sj. It has a width of pn#. The first element is s1=1, but the first prime is s2=pn+1. If we complete the formation ( the first row) to a rectangle with the height pn+1 generating the next stamp, in every row in this rectangle exactly one number is divisible by s2.

with elements sj. It has a width of pn#. The first element is s1=1, but the first prime is s2=pn+1. If we complete the formation ( the first row) to a rectangle with the height pn+1 generating the next stamp, in every row in this rectangle exactly one number is divisible by s2.

The numbers sj + k * pn# ; k=0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , pn+1 -1 are on one row of a stamp Spn# . The number pn# is the product of the primes p1, , , pn and pn+1 is not a divisor of pn#. All elements sj are smaller than pn#. By construction of a stamp s2 is the next prime number, therefore is s2 = pn+1. Either sj itself has the divisor s2 . Then the next number divisible by s2 is sj +pn+1 * pn# or sj has not the divisor s2 . Then s2 sj has the divisor s2 .

Theorem 2: For pn# > 2 is valid: The stamps are symmetric.

Proof: The oldest method to get the primes is

the sieve of Eratosthenes (approx. 300 BC.). The first number only divisible by itself and 1 is the 2, the first prime. First of all all multiples of 2 are eliminated. The next number which is not eliminated is the 3 and therefore it is the next prime number. All multiples of 3 are eliminated etc.. If we apply this method with the primes 2, 3, 5 and 7 up to 210, the product of these 4 primes and also eliminate the prime divisors, we get the stamp S7#. The same result we get by beginning with the four primes on 210 and going backwards and eliminating the multiples of the four prime divisors. Therefore the stamp is symmetric. The same result we get with the first 5 primes 2, . . . , 11 if we pass through the region up to 2310 = 11# forwards and backwards or in general for every product of primes pn# with n > 1.

![]() (

(![]() = quod erat demonstrandum)

= quod erat demonstrandum)

At 210 the 4 first primes meet together the first time again. In the sieve of Eratosthenes the primes are inserted at 0 and all primes therefore don't touch the number 1. Corresponding to this the pass backwards up to 0 beginning at pn#, n > 2 the number pn# - 1 is never touched. Therefore 1 and pn# - 1 always belong to a stamp.

An estimation of the number of primes

A stamp contains all primes until pn# except the prime divisors. They are smaller than s2 . In addition a stamp contains the 1, which is not a prime. Therefore is valid:

Theorem 3: All elements sj of a

stamp ![]() form together with the elements

sj + k * pn# ; j = 1, . . . , m ; k = 1, 2, 3, . . . a group with the multiplication as operation.

form together with the elements

sj + k * pn# ; j = 1, . . . , m ; k = 1, 2, 3, . . . a group with the multiplication as operation.

Proof: The construction of the stamps first

eliminates the 2 and all numbers divisible by 2. The next step constructing S3# eliminates the prime 3 and its multiples etc.. By constructing a stamp Spn# all prime divisors and his multiples are eliminated. Every number t + pn in a stamp, which is not an element of the stamp is divisible by one of the prime divisors. Then the numbers t + k * pn# are divisible by one of the prime divisors. According to theorem 1 any number has exactly one representation in a product of primes. Therefore all elements of a stamp and its products are situated on the columns of the stamp Spn#.

![]()

For the smallest stamp S2# the property of such a group is well known: Products of odd numbers are odd.

Theorem 4: In every stamp Spn+1 the numbers < pn+12 are prime numbers.

Proof: The elements of a stamp are

representatives of the prime residue classes mod pn# from the residue-set {0, 1, 2, . . . , pn# - 1 }, which are coprime to pn#. In every stamp or this residue-set the first number is the 1, the unity. The second element s2 is pn+1. The smallest product which we can build in

this stamp is s22 and therefore all integer positive elements < s22.![]()

3. An Extension of Bertrands Postulate

Bertrand's Postulate is valid for primes:

Theorem 5: (Bertrands Postulate): For every n > 1 , n ∈ N there is at least one prime number between n and 2n.

This postulate is also listed in Wikipedia.

This theorem has been proved by P. L. Tschebyschow (1821-1894) and later on by J. S. Hadamard (1865-1963) and P. Erdös (1913-1996).

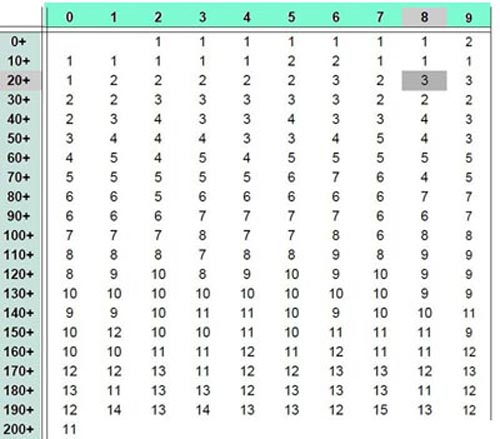

In the following I want to make a statement about the distance of two prime numbers which is more precise than Bertrand's postulate. For that at first the stamp S7# is examined. The results are appropriately applicable to all stamps. It is valid:

Theorem 6: In every interval of length 2pn - 2 with upper interval boundary < pn+12 there is at least one prime number.

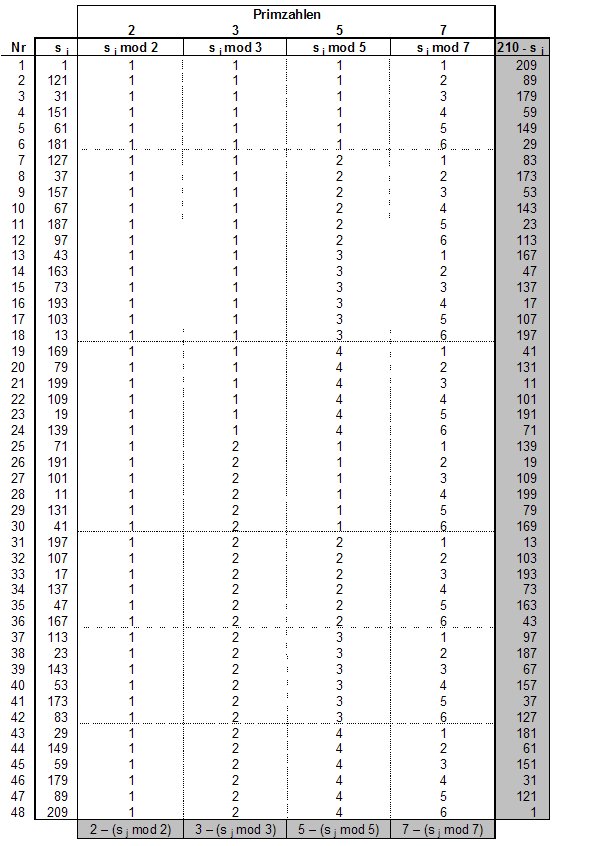

Proof : I will begin with the stamp S7# and will show there properties which are also valid for higher stamps. If we compute the modulo-function with the first four primes 2, 3, 5 and 7 in the interval untils 210, we get for the numbers 1 until 210 different results. For the number 63 for example we get the results 63 mod 2 = 1, 63 mod 3 = 0, 63 mod 5 = 3 and 63 mod 7 = 0. I name this result as quadruple {1, 0, 3, 0}. For a number coprime to the first 4 primes, 89 for example we get the quadruple {1, 2, 4, 5}. Because the number 89 is coprime, all 4 numbers are 6 ≠ 0. The stamp S7# is symmetric in 210, therefore we get for 121, the symmetric number. 1 to 89 the result {1, 1, 1, 2}, i. e. numbers adding with the quadruple of 89 result in the quadruple {2, 3, 5, 7}. These are again the 4 primes. For 147, the number symmetric to 63 we get the result {1, 0, 2, 0}. The corresponding sums are equal to pi or to mod pi.

Remark: The number 121 is not prime but coprime to and therefore an element from S7# .

The elements sj of S7# and their quadruples are listed in table 6. In S7# every possible combination of modulo-values can be found exactly once. This is a consequence of the Chinese remainder theorem. The modulo-values are the remainders to previous multiples of the primes 2, 3, 5 and 7. The functions pi - (sj mod pi) are the differences to the following multiples of pi. Because of the symmetric position of the elements sj in S7# is valid:

This means: For the numbers 210 - sj symmetric to sj we get the differences to the following multiples from the same table (column 210-sj and lowest row (grey underlayed). The consequence of this is that the greatest difference of one element of S7# to a multiple of of p4 = 7 can be p4 - 1, i.e. 6. This is valid as well for the difference to the following sj+1 as for the differnce to the previous sj . Therefore is valid: The greatest difference between two elements sj and sj+1 is 2p4 - 2 = 12 und daher liegt in jedem Intervall der Größe 2ps4 - 2 is at least sj.

Also between every multiple of pn+1, here 11 until the square 121 exist at least one prime number.

In the stamp S7# between every multiple of 7 exists at least one element sj. According the chinese residue theorem this is not valid for every stamp ![]() or every sj in the complete intervall of the stamp.

Because of theorem 4 we can limit ourselves in

or every sj in the complete intervall of the stamp.

Because of theorem 4 we can limit ourselves in ![]() to the range

≤ p2n+1.

to the range

≤ p2n+1.

Regarding the stamp S2# we see:

All odd numbers up to the square of the next prime 3 are primes.

Not till the 9, the square of the next prime 3, this number becomes active, to remove multiples of 3 according to the sieve of Eratosthenes. This is also valid for the next prime number 5 which will be active at 25 (Fig. 2). All products with 5 less 25 are removed by multiples of the primes 2 and 3. Accordant is valid for all other stamps. Therefore the stamp S3# for example is repeated until p22 = 25.

If we pass the the next stamp except the number pn+1 which becomes prime divisor up to pn+22 exactly 2 numbers are removed from the stamp: pn+12 and pn+1 * pn+2. These sj beeing between pn+12 and pn+1 * pn+2 must be prime as well as these sj beeing between pn+1 * pn+2 and pn+22 liegen.

According to these explained properties it is sufficient to proof:

Theorem 7: For n > 2 is valid: Up to n2 between every multiple of n is at least one prime number.

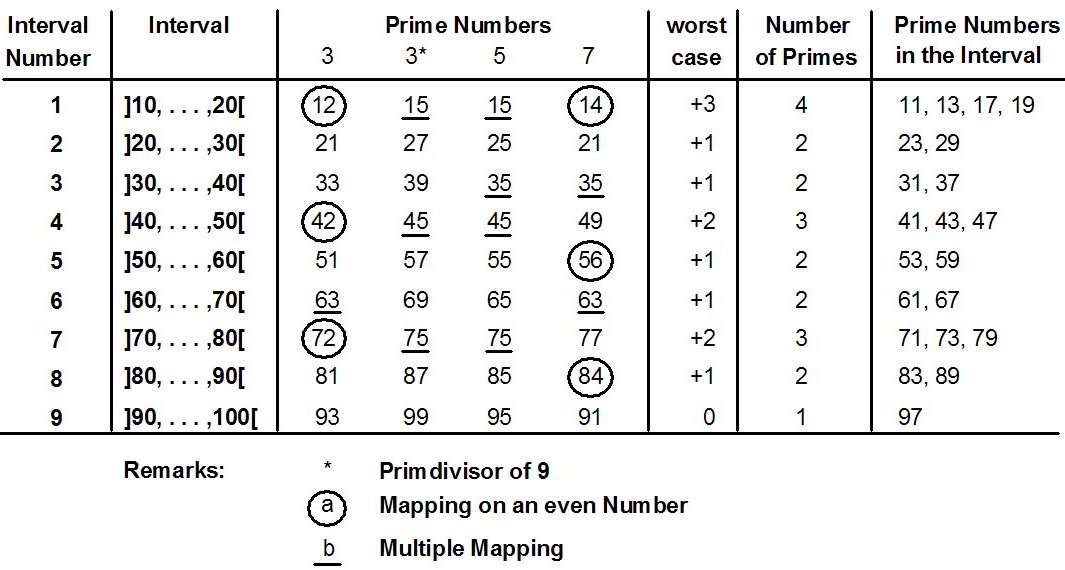

Proof: I will begin with an example from the prime numbers. I select the stamp S7# the square of the prime 11 and there the interval ]99, . . . ,110[ is examined. The boundaries of the interval are to consecutive multiples of 11. This interval should contain as stated at least one prime number. The interval has 6 even and 6 odd numbers.

Remark: With ]a, . . . ,b[ an interval is named which contains the numbers greater than a and less then b.The numbers a and b do not belong to this set.

The even numbers are removed by multiples of 2 and for the odd numbers is valid: Maximal 2 of these can be removed by multiples of 3, maximal one by multiples of 5 and 7 each. This is the worst case that can occur. Therefore from the 5 odd numbers remains at least one. It must be a prime. This is valid for all intervals ](i-1) * 11, . . . ,i * 11[ for i = 1, . . . ,11. I have chosen here an interval greater 49. For intervals with upper boundary less 49 the number of primes in such an interval increases. Thus the assumption that between to consecutive multiples of 11 up to the square 121 is no prime number leads to a contradiction.

We have here a multiplicative mapping of the odd numbers less than pn to every interval ](i - 1) * pn, . . . , i * pn[ for i = 2, . . . ,pn. An odd number which is not prime maps thereby with one of its prime divisors. But there is one exception: The 1, the identity element can't execute a multiplicative mapping. If in the interval only different odd numbers are hit, we have the worst case: One odd number remains which must be a prime number. If in this relation also even numbers are hit or odd numbers multiple are hit, the number of primes in the interval increases correspondingly.

In contrast to addition with the 0 as the neutral element at the multiplication the neutral element 1 belongs to the positive integer numbers and is odd. This has an effect on the upper intervals. The already existing primes are matched to the lower intervals.

This is not only valid for prime numbers, but for all odd numbers > 1. Now to the intervals with even boundaries: an interval ]n, . . . ,2n[ with n even contains as much odd numbers as the interval ]n+1, . . . ,2(n+1)*n[. An example for intervals with even numbers as interval boundaries if given in figure 7. It is common knowlege, that in every interval ]10, . . . , 20[ , ]20, . . . , 30[ until ]90, . . . , 100[ is at least one prime number. Theorem 7 declares the reason.

In every interval there is a mapping of the odd numbers 3, 5, 7 and 9. The number 1 can't map and the number 9 is mapping by itself or one of its divisors. In the ninth interval ]90, . . . , 100[ the mapping hits on different odd numbers therefore we have there the worst case, i. e there is only one prime number. In the 8. interval the 7 maps on a even number, all other maps are odd and different. There are 2 primes. Another example is the third interval. There the numbers 5 and 7 map on the same number 35 and therefore here are 2 numbers also. All intervals with products uj * uk < 10; odd and uk < 10; odd and uj * uk ≠ 10 contains more then one prime number.

At the intervals ]11, . . . ,22[ etc. the interval wirh the smallest number of primes is the interval ]110, . . . ,121[ with the prime 113. Now back the the higher intervals above mentioned. Here we have many different products of odd numbers uj and uk with uj < 1000 and uk < 1000 which are between 1000 and 1 000 000 and are unequal piun with pi < 1000. Likewise there are some prime numbers less than 1000, that means those between 500 and 1000. Nearly the half of these prime maps in an interval only once in fact on an even number. A lot of the other half maps in the next interval only on an even number. Therefore the worst case can't occur, i.e every interval contains more than one prime number. The intervals of the size 21, i.e. the intervals ]21, . . . , 42[ , ]42, . . . , 63[ until ]420, . . . , 441[ have already at least 2 prime numbers, in the intervals of the size 100 there are at least 7 and in the intervals of the size 500 there are at least 26 prime numbers.

It is suffcient to examine the intervals up to 1 000 000. This has several reasons:

| 1. | The " 1 " doesn't map. |

| 2. | With the

function x/ln(x) the number of primes is estimated.

>Then the number of primes in the interval ]x2 -x, . . . ,x2[ can estimated with

This function is an ascending function (for x > 2), i.e. the number of primes in these intervals is gradually ascending. |

Table 8 shows the minimal number of primes in the intervals until ]39 800, . . . ,40 000[. In the first row the numbers 0, 1, . . . ,9 are entered, in the first row the numbers 0, 10, . . . ,200.

As an example in the topmost row the number 8 is marked with an grey background. At the numbers in the first column the number 20 has an grey background. At the intersection of the row beginning with 20 an the column beginning with 8 (20+8=28) the number 3 is entered. This number indicates that in every of the intervals ]28, . . . , 2*28[, ]2*28, . . . ,3*28[ until the interval ]27*28, . . ,28*28[ are at least 3 primes. Another example: The number 11 in the last row means: Every interval ]200, . . . ,400[, ]400, . . . ,600[, ]600, . . . ,800[ , . . . , ]39.800, . . . ,40.000[ contains at least 11 primes.

Looking with a table of prime numbers at higher intervals,

for example the intervals ]1000, . . . , 2000[ bis ]999 000, . . . ,1 000 000[, we find in every interval more than 50 prime numbers.

The theorem 7 proves theorem 6 also. The theorem is helpful for some problems of prime numbers.

Until p2 the distance of two adjacent

prime numbers is < 2n.

Duality: With theorem 4 and theorem 7 we have dual theorems: At the integers >: 1 of the prime residue group (Z/pn#Z)* there are up

to pn+12 only primes and between every multiple of pn+1 there exists up to pn+12 at least one prime.

At large numbers it happens that we know a prime number, we call it pn+1 for the moment but the previous prime number pn we don't know. Because pn+1 - pn ≥ 2 is valid and if we now substitute n for n+1 the following statement is also valid:

Theorem 8: Let be n and n+1 two natural numbers > 1. Then there are between n2 and (n+1)2 at least 2 prime numbers.

Proof:

1. Between 1 and 4 there are 2 prime numbers : 2 and 3.

2. Starting with n2, there are 2 additional intervals +1 necessary to archieve (n+1)2. The primes of these two intervals are the result of the odd numbers 1, 3, 5, . . . , m, with m < n . In every of these intervals is therefore at least one prime number. Regarding these two additional intervals, we get a change of some values in figure 8 the table until 200*200. Here the 2 in the first row, column 9 ist changed to an 1. Here the 9 (or the second 3) is not yet inside the interval. In the interval ]72, . . . ,81[ for example the two numbers 3 and 5 hit the same number 75. Because the 1 doesn't map there are two primes in this interval, 73 and 79. First in the interval ]90, . . . ,99[ the waste case is found, i.e. There only one prime number 97 is located. Further changes to figure 8 are found at 70+7, i.e. 772, at 110+9, i.e. 1192 and at 170+8, i.e. 1782.

![]()

(See also Legendre's conjecture and Brocard's conjecture)

Also in the two intervals ]99, . . . , 108[ and ]108, . . . , 117[ are prime or odd numbers that are divisible by 3, 5, or 7. This will only change in the next Interval containing the number 121 = 11 x 11. So this is e.g. B. also with the intervals ]90, . . . , 100[ the case. Here too we have with the interval ]120, . . . , 130[ a new situation. The upper bounds of the intervals are each smaller than the nearest p2.

In the algorithm in section 5 appears that with n2 and the primes ≤ n2 the primes respectively the prime factors until (n+1)2 without division can be computed.

4. Goldbachs Conjecture

In 1742 C. Goldbach (1690-1764) remarked in a letter to L. Euler (1707-1783) the conjecture, whether every odd natural number n > 5 can be written as a sum of three prime numbers or whether every even natural number n > 4 can be written as a sum of two prime numbers? Both sentences are known as Goldbach's conjecture.

There are several attempts to prove this conjecture. This is therefore difficult because prime numbers arise from formation of products and thev formation of a sum cannot be brought about to connection with that.

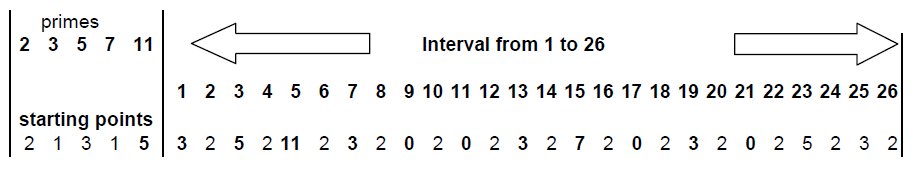

At first a graphic representation shall give a general idea. I show the numbers in a straight line in the horizontal and draw in the prime numbers. They are marked as black points in the topmost row.

We form a matrix of the natural numbers of 1 to n . We then mark the prime numbers in a vertical direction in any column which starts with a prime number. We mark the prime numbers also in the first column. We therefore get a symmetric picture of the prime numbers. In figure 9 every fifth number is drawn on the top and on the left side.

In the drawing every tenth line is solid for better orientation, the 50th line is a little thicker. A diagonal of 225°(= 45°) beginning at an odd number 2n - 1 in the first row through this numeric array hits prime numbers. One can immediately read solutions for Goldbach's conjecture here. The diagonal which starts at 127 for example hits the number 19 at 109. This two numbers are prime numbers in accordance with the construction and its sum is 128. Going on at the diagonal we get the intersection point 31 at 97, with the sum 128 also and the intersection point 61 at 67.

To find solutions for Goldbach's conjecture, we must start

at an odd number with the diagonal because the drawing doesn't contain the zero-row but starts with the number 1. We notice that for diagonals starting at a prime number it is more diffcult to find an intersection point than diagonals starting at an odd number which isn't a prime. This is a way for looking at the problem.

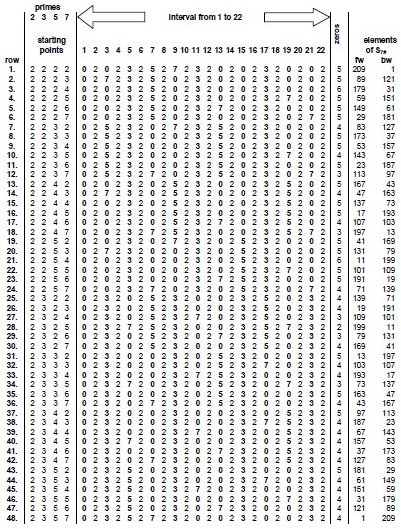

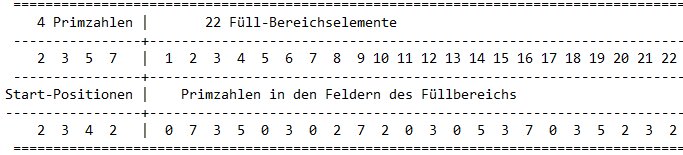

We have shown in the previous chapter that at least 2 prime numbers lie in every interval of the size 2pn+1. We want to fix one of these prime numbers now. If we do that we still have at least one prime number in the mentioned interval. We want to demonstrate this at the example with the first 4 prime numbers 2, 3, 5 and 7. The filling aerea then has the size 22.

One of the prime numbers is fixed on the 1, i.e. we use the numbers 2, 3, 5 and 7 only in such a way that they don't hit on the 1. Then we can allow the 2 only starting at the 2. The prime number 3 we can also allow to have its starting position on the number 2. It then hits 2, 5, 8 etc. . We however also can put it on 3. It then meets 3, 6, 9 and the other multiples of 3. According to this procedure the prime number 5 can be allowed to start at 2, 3, 4 or 5 and the prime number 7 can be allowed to start at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. There is the following rule in the algorithm : If a field in a row is filled with a number > 0 then the field is not changed if a new number will will the same field. This rule is not necessary, it is only for better understanding of figure 10.

Altogether 48 filling areas arise in this way. This is shown in table 10. The first row in the range of 1 to 22 of the table is made as follows: At first the range of 1 to 22 is made empty, i.e. filled with zeros. The prime number 2 is used on 2. The number 2 and its multiples fill the numbers 2, 4, 6, . . . , 22. The prime number 3 is also used on 2. It and its multiples fill then the numbers 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17 and 20. The prime number 5 is also used on 2, just as the prime number 7. The fist row is now completed. In the second row, with the prime numbers 2, 5 and 7, we proceed just as in the 1st row. Merely the prime number 3 starts on position 3. It and its multiples then occupy the fields 3, 6, 9, 12, . . . ,21. In a corresponding way the additional rows are made. The last row is remarkable. The prime numbers are used exactly just like we know it from the sieve of the Eratosthenes. As we see there are 48 possibilities and therefore we can have a try to assign these to the elements sj of S7#. At first to the last row. It can undoubtedly be assigned to the element 1 of S7#. The elements in S7# aren't divisible by the first 4 prime numbers as we know. Furthermore every element has the following property: It has a definite difference to the next multiple of the prime numbers 2, 3, 5 and 7. I would like to explain this in two examples:

Example 1: For the element 83 the next multiples of 2, 3, 5 and 7 lie at 84, 84, 85 and 84. so the differences to 83 are 1, 1, 2 and 1. These correspond to the starting points 2, 2, 3 and 2 in figure 8. This is the seventh row. Therefore the 83 is there registered under fw (=forward).

Example 2: For the element 43 the next multiples of 2, 3, 5 and 7 are 44, 45, 45 and 49. The differences to 43 therefore are 1, 2, 2 and 6, i.e. they correspond the starting points of 2, 3, 3 and 7. This is the 36th row. Hence the number 43 is registered under fw.

In this way the entries in column fw (=forward) can be found for all elements of S7#. In the same way the differences to the next lower multiples of P7 = {2, 3, 5, 7} in S7# can be determined. They are listed in the column bw (=backward). Because of the symmetry of S7# they also can be computed as bw = 7# - fw. Since the assignment of a row of figure 10 to an element of S7# is unique, we can draw the conclusion also in the opposite direction: To every element bw from S7# only one row of the table 10 can be assigned. There is at least one prime number in the interval from 1 to 22 in every row of table 10. The number bw assigned to this row hits an element sj of S7# . It holds:

In an example we compare the results of figure 10 with figure 9. One of the diagonals marked starts at 97. A comparison with the results of table 10, row 12 (bw = 97) shows: The first zero in the interval 2 to 22 is on position 9 (no prime number) corresponds to the crossing of the diagonal at 89. The next zero on position 15 (no prime number) corresponds to the crossing of the diagonal at 83. The next zero on position 19 (prime number) corresponds to the hitting of the diagonal at 79.

Beginning with the subset P7 = {2, 3, 5, 7} of primes in the corresponding stamp/prime residue classes all numbers less then 121, the square of the next prime number are prime. Corresponing statement ist valid for the numbers of figure 10. Here only the values greater than 49 are of interest. In summary, the statement: in the filling aerea 2, . . . ,2pi+1 is at least one prime number, we can apply only for the primes between 49 and 121.

Figure 10 is an example for the prime numbers P7 = {2, 3, 5, 7} of the stamp S7#. The construction of such a table can also be carried out for every higher stamp. In accordance with theorem 4, sj is a prime number if sj < s2. By a suitable choice 3 of a higher stamp we can achieve that sj is a prime number in (1).

Remark: If we look at larger prime number pi = 16000057 for example, this is contained in the stamp S23# 23# = 22309870 is greater than pii . The next prime number to 23 is 29. This however doesn't mean that the next even number 16 000 058 has to be a sum of 2 primes one of them is smaller than 58(= 2pk). Only if we use a stamp S3989#, all numbers in the stamp which are smaller than 16 000 057 are prime numbers. Then the second element of the stamp is s2 = 4001 and all stamp elements < 40012 = 16008001 are prime numbers. Then it must be a solution for the Goldbach's conjecture one of the two prime numbers is smaller than 8002.

We have seen now that an element of S7# corresponds to a variation of the base prime numbers pi = 2, 3, 5, 7; pi, (i = 1, . . . n); n = 4 under the condition that a prime number is fixated. At least another prime number lies in the range of 2 to 22 (= 2pi+1) if the other is fixated. From this follows that a solution of Goldbach's conjecture for the corresponding element which is listed in the bw also exists and to be more precise in the range of 2pi+1, the filling aerea.

Further solutions of the Goldbach problem are possible,

at which the lower of the two prime numbers is greater than 2pi+1. There is rather at least one solution, wherein the lower of the two numbers is less then 2pi+1.

For higher numbers a corresponding table like table 10 can be

constructed and determined the values fw and bw in the same way. An element sj of the stamp and one in the interval 2pi+1 existing prime number form the sought-after sum, if in the stamp only numbers < pi+12 are elected.

By fixation on the 1 in figure 10 it becomes appearent (similiar as in theorem 7): We have here a multiplicative mapping of the primes up to 7 on the stamp S7#. The mapping of the 1 is by the construction explicitly excluded (except in the last column), i. e. the products 1*3, 2*3, 3*3, etc., as well as 1*5, 2*5, 3*5 and 1*7, 2*7, 3*7 are excluded. From that follows that in every of the 48 combinations not only products of the numbers 3, 5 and 7 can be found, but at least one number is not such a product and therefore a prime number.

By a suitable choice of the stamp it can be reached that sj < sj2 and therefore a prime number. For even numbers 2n, when 2n - 1 is a prime, the assertion is proved.

The second case: 2n - 1 is not a prime number. We look at a

stamp ![]() again and in it at the prime numbers < pn+12 =s2. Let pj such a prime number. It was demonstrated in case 1 that pj+1 is the sum of 2 prime numbers. By addition of pj and the primes < 2pn+1 we get the even numbers until to the next prime number. In the interval [1, . . . , 2pn+1] however not all odd numbers are prime. There also here are products of the base-primes. These are the numbers 9, 15, 21, . . . . As we can fixate one prime number on the 1 we can fix a prime number on any odd number in the interval 2pi+1 and at least one number in this interval remains as prime. The fixation on the prime numbers 3, 5, 7, etc. is unnecessary because these numbers together with pj fullfills Goldbach's conjecture. If we carry out the fixation on one of the numbers 9, 15, . . . , we get a prime number < 2pn+1 which together with a prime number < pj fullfils Goldbach's conjecture. This completes the proof of Goldbach's conjecture.

again and in it at the prime numbers < pn+12 =s2. Let pj such a prime number. It was demonstrated in case 1 that pj+1 is the sum of 2 prime numbers. By addition of pj and the primes < 2pn+1 we get the even numbers until to the next prime number. In the interval [1, . . . , 2pn+1] however not all odd numbers are prime. There also here are products of the base-primes. These are the numbers 9, 15, 21, . . . . As we can fixate one prime number on the 1 we can fix a prime number on any odd number in the interval 2pi+1 and at least one number in this interval remains as prime. The fixation on the prime numbers 3, 5, 7, etc. is unnecessary because these numbers together with pj fullfills Goldbach's conjecture. If we carry out the fixation on one of the numbers 9, 15, . . . , we get a prime number < 2pn+1 which together with a prime number < pj fullfils Goldbach's conjecture. This completes the proof of Goldbach's conjecture.

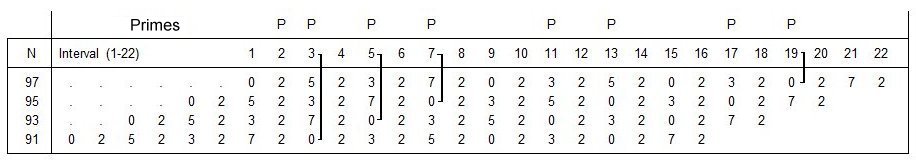

The proof of the second part can be simplified : The results before have shown that the solution of goldbachs conjecture deals with the residues rj of a prime pj to the base-primes p1, p2, p3, . . . ,pk. The the residues of the number pj - 2 relative to the base-primes are the numbers rj - 2 or pj - rj - 2, if rj < 2. For pj - 2 one could carry out a fixation. Asuming that pj - 2 is not a prime the diagonal in figure 9 beginning at pj must be rised at 2. Then the diagonal for pj - 2 begins at -1 with the same sequence of base-primes and zeroes as computed at pj. Then the resulting interval for pj-2 is [ -1, . . . ,2pn+1 - 2] instead of [ 1, . . . ,2pn+1]. This subtraction of 2 is repeated until the previous prime pj-1 is reached, i.e. the first zero in the sequence is reached. Then the action described in the first part of the proof begins again. This is demonstrated for the numbers 98, 96, 94 and 92 in figure 11.

I will demonstrate this fixiation on an example. We look at the number 147. It has the prime representation 3 * 7 * 7 . The greatest prime number < 147 is 139. Drawing a diagonal with 45° beginning at 147 (Fig. 9) intersects the number 139 at 9. The number 147 is in the interval in which all primes are generated by the base-primes 2, 3, 5, 7 and 11. We will therefore vary these 5 base-primes in the interval [1, . . . ,26] , that they not hit the number 9: The number 2 always must start at 2. The number 3 must start at 1 or 2 but not on 3 because then it would hit the 9. The number 5 can start at 1, 2, 3 and 5. Accordingly the number 7 on 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and the number 11 on 1, 2, 3, . . . , 8, 10 and 11. Totaly the are 480 variations. Not all of these variations are listed in figure 12 but only the one of interest.

The differences of 147 to the preceding multipes of 2, 3, 5, 7 and 11 are 1, 0, 2, 0 and 4. This corresponds to the selected positions of action in figure 9. The primes 11 and 17 are not hit. They correspond to the primes 137 and 131 if we follow further the diagonal beginning at 147.

It isn't necessary to build the table of all possibilities to find the sought-afterprime number for Goldbach's conjecture. For the algorithm it rather suffices to find the prime factors of 2n - 1 and the idfferences of 2n - 1 to the preceding multiples of the base primes numbers which are not prime factors of 2n - 1 i.e. the remainders of 2n - 1 with regard to the base-primes. With these numbers we can determine the starting positions for a computation like that in figure 10. The prime numbers pa there which are marked with a zero are together with 2n - a solutions of Goldbach's conjecture for 2n.

Goldbach's numbers must so to speak pass 2 sieves behind each other. The first sieve is the sieve of Eratosthenes at which all prime numbers start at zero. The second sieve is built up similarly as the first one but the base prime numbers don't start its run all at zero but at other starting positions, which can be computed with the remainders of 2n - 1 .

Sierpinksi mentions in his book about the theory of the numbers [Waclaw Sierpinski: Grundlegende Theorie der Zahlen, Wasawa 1964] in the section over Goldbach's conjecture the problem of the differences of prime numbers. Using the above explanations the theorem, that every even number is the difference of two prime numbers also can be proved with the help of the numbers fw and the diagonals in the direction of the 315° (not marked in fig. 9).

5. An algorithm for computing prime numbers

In the previous section the elements of S7# and in figure 6 the residues resi are listed. With figure 12, the table with the fixation of one prime number to position 1, the starting positions ( they are named now posi ) of the 4 prime residues 2, 3, 5 and 7 are showed. The number of these prime divisors i.e. "base-prime numbers" is n=4 for the moment. They lead in every line to a fixation on the number 1. A comparison of the both tables shows, that the values of resi and posi differ by 1. There is posi = resi + 1.

The zeros in the filling area i.e. the zeros in a line of figure 12 indicate, where - starting on an element sk of S7# a previous element of S7# is situated. For the element sk, which are less than 121, the square of the next prime number this means that we in S7# with this method one can find prime elements. This is valid at least until 49, the square of prime number 7.

Conversely because of symmetry of the stamps/prime residue classes the prime numbers following the element sk can be found. For that the starting positions in a line of table 10 must be differently elected. They must by be especially complementary to the described values. We must elect as starting positions the values posi = pi - resi + 1 and apply the algorithm described in the previous section.

An array-element of the filling aerea can multiple occupied by prime residues. In the previous section onlya single occupation of a field-element was admitted. This was only practised to clarify the algorithm. To accelerate the algorithm one can leave out this examination and in addition restrict to the array-elements with odd array-index only.

The number of array-elements of a filling aerea is for the moment 2pi+1. If the filling aerea is mapping an area, in which the square pn+12 is situated, the corresponing element in the filling aerea is zero also. The element corresponds not with a prime and must be ejected.

The last zero one can find in the filling-aerea 1, . . . , 2pi+1 marks the prime number pneu, if it will not correspond the prime-square p2n+1. With this new prime number we can continue in the next step. We compute the difference to the previous starting value and add the difference to every of the residues resi.

After crossing p2n+1 (here=121) we are going to the next stamp, i. e. in the example to S11# and prime number 11 is admitted to the "base-prime numbers". The the number of "base-prime numbers" is n=5. The residue res5 for 11 at 121 is zero. The the number of the array elements of the filling aerea becomes 26. The residue res5 for 11 at 121 is zero.

This however is the only number, one must pay attention during the election. Alltogether we need at the computing of prime numbers with this method only a few dividing operations. We have to fill a 2pi+1-area ( Filling-Area ) with the base primes pi and the prime numbers are falling out like the balls from a gumball machine. Only on one number we must have attention, p2n+1. It is not a prime number but this number increases, if crossed, the number of base primes by 1 and increases the filling aerea.

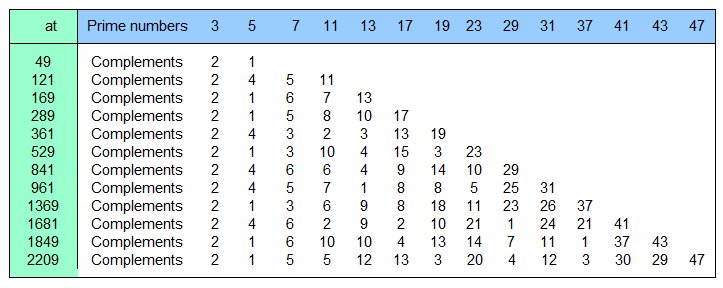

I will demonstrate the algorithm by an example: I begin with the prime number 97. The prime numbers < √97 are 2, 3, 5 and 7. They are in the figures 11 and 12 the base prime-numbers. The next prime number is 11. The number of the elements of the filling aerea is 2 * 11 = 22. The residues of 97 relatively to 2, 3, 5 and 7 are 1, 1, 2 and 6. We compute the complements. They are 1, 2, 3 and 1. (The algorithm can begin at any number ≥ pn2 (here ≥ = 49), if there the residues or complements to the primes p1, . . . ,pn are known and the next boundary pn+12 (here = 121) is respected.) Alltogether summarized for starting value 97 in table 13.

The values "Complement" + 1 are the starting positions for the algorithm described in the previous section. In table 13 one can see the result. Here is - except the first value - the 5., 7., 11., 13. and 17. value zero. That means: 101, 103, 107, 109 and 113 are prime numbers.

The last prime number of the series is 113. It is the starting value for the next computing step. By computing with the modulo-function or by subtraction at the end of the filling-aerea the residues and their complements can be computed at the last prime of the filling aerea. These complements are the new starting positions, etc..

With 113 as starting value we get the resulting primes 127 and 131. Also the 9. Value, which corresponds to the number 121 contains a zero. This we had exspected and this value is ejected (i.e. is not prime) The next such value would be 143, the product 11 * 13. This however is out ot the filling aerea. Two primes 127 and 131 are crossing the prime-square 121 and the next computing step with the 131 as the starting value contains the 5 base primes 2, 3, 5, 7 and 11 and the numbers of array-elements is 26. The residue of 131 relatively to 11 is 10. This is computed as the difference to the prime-square 121.

The algorithm requires 20 steps from 97 to 811 and there are 116 prime numbers, 40 steps from 97 to 2221 and there are 311 prime numbers.

One can improve the algorithm: If the difference pn+1 - pn is greater 2pn, the filling aerea can be increased. That's also possible to organize the filling aerea in the algorithm that in one computing step all primes between pn2 and pn+12 are found.

6 An algorithm for prime factorization

In the preceding section is shown how from a filling aera primes can be taken. On the coresponding positions zeros are found. The other positions in the filling aerea contain primes. These entries are prime factors of the corresponding number. Therefore we must choose the filling aerea that the number z whose prime factors we want to compute is situated between two primes-squares following each other. From the previous section is evident that not only primes are indicated by a zero but also squares of primes. We are here for example in the group of prime residue classes (Z/210Z)* or in other words in the stamp S7#. There pn2 = 121 and pn+12 = 169 are elements also. Therefore we must choose pn2 and pn+12 that pn2 < z < pn+12. The corresponding filling aerea can begin at pn2 and end at pn+12 or earliest end at z. The true filling aerea begins always at 1 as shown above. After filling the entries at z - respective the position in the filling aerea which corresponds to z - are prime factors of z.

One has to continue from prime-square to the next prime-square until the condition mentioned above is fulfilled. At the end of every filling aerea, i.e. the interval [ pn2, . . . , pn+12], the residues and complements for the next computing step are determined. The base-prime numbers are increased by one prime number.

Of course we get not all prime factors. Multiple entries of a prime factor can not be entries at the element corresponding z. Also prime factors > are not entered.

It would be an immense computational effort to compute all primes beginning at the first. Thefore is recommended at certain distances to store the complements. For example at the j-th prime pj2 to store all complements, which are necessary to continue the computing at pj2. .

Imagine the primes orderd in horizontal lines: On the first line the prime 2 lies located and is repeated at 4, 6, 8, . . . . The prime number 3 is located in the next line. It is repeated at 3, 6, 9, . . . . In corresponing with the following primes the same is done. On the i-th line the prime pi is situated and is repeated at 2p>i, 3p>i, . . . . Every prime p>i brings an influence to the forming of primes starting at pi2 . With the forth prime for example we find that the numbers 49, 77 and 91 are not belong to the primes.

The presented algoritm takes a vertical cut across these lines. This cut reaches always until the i-th line. For the numbers ≥ 49 until numbers < 121 for example this cut is performed until the forth line. Hits this cut not an entry then the number is a prime. Hits the cut however one or more numbers, the these numbers are prime divisors. At every cut a prime divisor occurs only once.

In the algorithm on can add several corrections to accelerate the computing procedure:

Going without the prime factors of the even numbers one can leave out the even numbers in the filling aerea. Similiar the numbers which have the the prime factors 3, 5, 7 and others. I refer hereto on the criteria of divisibility in [ Prof. Dr. Harald Scheid: Zahlentheorie, ISBN 3-411-14841-19], p. 121 ff.

Because at the filling every second number is even, on can hurry up the algorithm leaving out at these positions.

If the primes and complements at pi2 are computed and stored, sometimes it make sense to pass the computing-process backwards, if e.g. the prime factors for a number between pi-12 and pi2 should be found.

Further activities are possible to accelerate the algorithm.

If the filling aerea is too large and can't handled as a whole in the computing program, it can be divided in severals parts.

If the primes > pi+1 are not of interest, the procedure can be continued, until the primes pi+1 are found. Then pi2 greater than i+1 is reached and the residues and complements there are known. Now the residues at pi2 relating the base-primes can be computed in another way. Then the prime factors in the filling aerea [pi2,. . . , pi+12 are computed in the manner described above.

6.1 Example of Computation of a Prime Factor

In the following example, a prime divisor of the number 10117 will be calculated. Let only the prime numbers < 49 = 72 be known. These prime numbers are stored in a file "FileP1.txt". The remainders or complements of the primes 2, 3, 5 and 7 at 49 are calculated. I have defined the complement as compi = pi − remainderi, i.e. the number 49 for example and pi = 5 then is 49 mod 5 = 4 and the next multiple of 5 is 50. Therefore here the complement is 1. The complements at 49 for the primes 2, 3, 5 and 7 are 1, 2, 1 and 7. The next prime is 11 and its square is 121. The difference 121 - 49 = 72 and therefore a fill area created for these elements has 73 elements. The even numbers are ignored. Therefore only the 1., 3., 5., . . . of the filling area calculated. This fill area is first emptied, i.e. all these elements are set to zero. Then the filling of the filling area beginsThe 3 has the complement 2 and fills the fields 3, 6, 9, . . . , the 5 has the complement 1 and fills the fields 2, 7, 12, . .. . Accordingly the 7 fills the fields 8, 15, 22, . . . . After all fields are occupied, for the sake of completeness the first element with 7 and the last element with 11.

Now the evaluation of the filling area begins. All fields that have not been occupied correspond to the prime numbers in the range 49 to 121. They are stored in the file "FileP2.txt". The complements at 73 (in the filling range) or 121 are calculated. It can be obtained as follows: If the upper limit of 73 is exceeded by a multiple of a prime number during filling, then the complement results from the difference of this number - 73. With these complements start in the following fill aerea. To do this, the next prime number is read from "FileP1.txt". It is the 13. This filling range should accommodate the elements from 121 to 169 = 132. It has 49 elements. The elements of the fill area are set to zero and then with the help of the complements calculated at 121 the new fill area is filled. In addition to the complements of the numbers 3, 5, 7, the 11 is now added. It has the complement 11 (or 0) at 121. Again, the prime numbers result from the elements that have not been occupied. In the file "FileP2.txt" these prime numbers are added.

This procedure continues - initially until all prime numbers from "FileP1.txt" are used up. Figure 1 shows the squares of the prime numbers and the associated complements up to 472, i.e. up to 2209. Per line, the squares of the prime numbers and the complements of the prime numbers at these squares are listed. Now "FileP1.txt" is supplemented by the values from "FileP2.txt". After that, the file "FileP2.txt" is deleted and filled with the new prime numbers that are determined with the continuation of the procedure.

Table 15 lists the complements of the prime numbers in the squares of the prime numbers. The square 169 is smaller than the searched number 10177, which is to be broken down into prime dividers. Therefore, the next filling range is calculated. It is first emptied and filled with the prime numbers with the help of the complements. The resulting prime numbers are added to the prime numbers present in the "FileP2.txt" file. Continue with this method until all prime numbers from "FileP1.txt" are processed. This is the case with the prime number 47. Thus, the prime numbers from 53 to 2207, the largest prime number less than 472, are stored in file "FileP2.txt".

It is noticeable that with for prime number 3, a 2 appears as a complement every time. For p2 > 9 the following applies: pn2 – 1 is divisible by 24, i.e. also by 3. Because of this this result appears here.

If while filling the aera with a prime upper limit is exceeded, the complement of this prime number is known from the difference to the upper limit. As no calculation of the complement is required by the modulo function.

If you continue in this way, you finally reach the number range in which pi2 ≤ 10117 ≤ pi+12. This is the range between 972 and 1012. Here, the filling area is evaluated more thoroughly. The result is shown in Table 2. Each element from the fill area corresponds to a number between pi2 and number range in which pi2 ≤ 10117 ≤ pi+12. This is the range between 972 and 1012. Here, the filling area is evaluated more thoroughly. The result is shown in Table 16. Each element from the fill area corresponds to a number between pi2 and pi+12. Starting at 72 it takes 13 intervals to get to the interval (972, . . . , 1012) and this interval contains what we are looking for the result.

Only the ungraded numbers are listed. Under "Index" the index from the fill area is displayed. Under "Number" the respective number between the prime number squares is listed and with "Prime factor" a prime factor is displayed. It is the smallest prime factor of the corresponding number. As you can see, 10117 has a prime factor of 67. With a small change in the algorithm, the largest prime factor < pi+1 (here < 101) or all prime factors < 101 can also be displayed. Each factor is then listed only once. This algorithm has also been used to find the prime numbers up to 10201. The prime square and complements of the prime square 10201 are stored in a file. This has the advantage that you can use it when searching for a prime divider of a larger number can fall back on these values and does not have to start again at 49. Of course, you can save it anywhere (preferably with a square of a prime number).

7 Comparison with the Zeta-Function

Comparing these results with Riemanns Zeta-Function the following is to note: The computation of the primes occurs between pi2 and pi+12, by using the previous results - the primes until pi and the residues resp. complements to the primes at pi2 are used to determine the primes until pi+12. With the algorithm described in the last chapter on p2i+1 meets no number i.e. it is initially a prime number. Only after the filling the field between pi2 and pi+12 the prime pi+1 is inscribed. At the Zeta-Function operating with the reziprocal values of the primes, the real part of the zeros have the value 1⁄2. This corresponds here in the described algorithm to a stop at the value pi+12. There the first time the prime pi+1 joins the game. Between the squares of consecutive primes, even between the squares of consecutive positive integers primes resides as shown with theorem 2. The computation of primes stops always only at pi+12 so as the Zeta-Function at a zero with the real part 1⁄2. There are no other complex zero points except such with real part 1⁄2. This proves Riemann's conjecture.

8 End

I would like to point out to Ulam's spiral here again mentioned already at the beginning. The squares of the odd numbers beginning at 1 lie in the diagonal to the top right. In the diagonal beginning at 4 to down on the left are the squares of the even numbers. From theorem 8 results that at a half turn of the spiral we reach one of these diagonals passing at least two prime numbers. A line vertical to this diagonale through the numbers 6, 20, 42, . . . , i.e. n2 - n, (n odd), respectively on the other side though through the numbers 12, 30, 56, . . . , i.e. n2 - n, (n even) marks the boundaries of the intervals. Between these boundaries and the squares there is at least one prime number.

On these points (one number later) the direction of the

Ulam-spiral is chanced by 90° rsp. by -90° depending on the spiral is drawn clockwise or counterclockwise.It is irrelevant whether the spiral begins with the 2 on the right, the left, above or below the 1. If the Ulam-spiral begins with zero in the center, then it changes the direction by 90° exactly at the edges.

If you agree my proves or you have found errors in it please send me an email.